Understanding and Measuring Anti-Intellectualism

Earlier this year, I developed and administered a survey in which I tried to tap into the elements of anti-intellectualism that appeared to be rising to the surface in Trump's rhetoric. Following Hofstadter's lead, I attempted to come up with a battery of questions designed elicit responses that indicated whether or not someone exhibited the resentment and suspicion he described.

However, one of the biggest criticisms of Hofstadter's analysis is that anti-intellectualism is a rather amorphous concept that can manifest itself in a number of ways. 25 years ago, Daniel Rigney, a sociologist at St. Mary's University dissected Hoftstadter's discussion of the socio-cultural roots of American anti-intellectualism and identified three separate, but interrelated dimensions:

- Populist Anti-Elitism – The belief that the values of intellect are, almost by definition, elitist in nature; that the educated classes are suspect, self-serving, and out-of-touch with the lives of “average Americans.”

- Unreflective Instrumentalism – The belief that the value of education is primarily found in the immediate, practical end of job training, and spurns the more abstract notions of expanding one’s horizons and developing a deeper understanding of the human condition.

- Religious Anti-Rationalism – The belief that science and rationality is emotionally sterile and promotes relativism by challenging the sanctity of absolute beliefs.

As relevant as these dimensions may be, it seems to me that they make up an incomplete list, particularly in the modern political context that has evolved since Rigney's analysis. In particular, it seems that a suspicion of science and those who engage in it need not necessarily be rooted in the centuries old struggle between religion and science. As evidence of that claim, I bring up the research of yet another sociologist, Gordon Gauchat. In 2012, Gauchat documented the decline of public confidence in the scientific community over the past four decades, particularly among those identifying themselves as politically conservative. While he demonstrates that the lack of confidence in science is significantly correlated with religiosity (it's often not what religion people believe, but how much they practice that religion that matters, so we will often measure religiosity as frequency of church attendance), he also showed that it was fairly clear that such skepticism of science was not simply due to the fact that religion and science are often at odds with each other.

While opposition to such things as teaching evolution in public schools can logically be connected to religiosity, the same cannot necessarily be said about other issues where public perceptions are often at odds with the conclusions of the scientific community. Battles over climate change and the safety of vaccinations and genetically modified organisms in food come to mind. Opposition to the evidence and conclusions presented by the scientific community on these issues seem less likely to be due to religious objections but simply due to a related, but distinct, fourth dimension of anti-intellectualism:

With these questions and others like them, I created four anti-intellectualism scales (one for each dimension) by taking the average score across the items within each dimension. I included these questions along with a series of other questions about the campaigns and the candidates running this year to a national sample of 1220 Americans from June through August earlier this year.

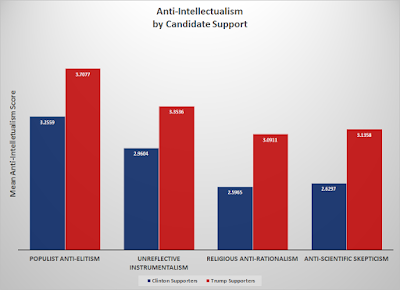

The results seem to confirm that Donald Trump's anti-intellectual/anti-establishment rhetoric appeared to strike a chord with a number of individuals. As the figure below shows, Trump supporters were significantly more likely than those supporting Clinton to hold anti-intellectual views on each dimension. (p < .001, which, in non-nerd speak, simply means that we can reasonably conclude that the differences we see here in the anti-intellectualism scores between Clinton and Trump supporters are real and not simply due to the fact that we only talked to 1220 people).

Using Anti-Intellectualism to Predict How a Person Will Vote

I took this a step further to see if we could use the anti-intellectualism scores to estimate the probability of supporting Donald Trump, while controlling for party identification. To put it more simply: We know that Republicans are more likely to support Donald Trump than either Independents and Democrats. Does anti-intellectualism make Independents, and even Democrats, more likely to support Donald Trump? Are Republicans who score low on the anti-intellectualism scale less likely to support him than fellow Republicans who score higher?

To answer those questions, I did some (more) nerdy stuff. I ran a logistic regression with the vote intention question as the dependent variable and party identification and the anti-intellectualism scales as independent variables Logistic regression is a statistical technique we nerds use when we want to see if certain variables (in this case a person's party identification and their anti-intellectualism scores) can help us predict what someone is going to do or say when they're given two choices. In this case, those two choices were either saying they were going to vote for Donald Trump, or for Hillary Clinton. (Yes, I know there were other choices, but there weren't enough people in my survey who said they were planning on voting for Gary Johnson, Jill Stein, or someone else... so this works).

Simply put, it's basically a more rigorous test of the influence of anti-intellectualism on a person's decision about who they were planning on voting for than the figure above. When I ran all the variables together as predictors of intended vote choice, only one of the anti-intellectualism dimensions ended up being a significant in addition to party identification: Populist Anti-Elitism.

The figure below shows how a person's party identification (whether they consider themselves a Democrat, Independent, or Republican) and their populist anti-elitism score effects the likelihood that they would indicate they were planning on voting for Donald Trump. Each line represents people in each party identification category. As the lines move across the chart to the right, it indicates people with higher anti-intellectualism scores, and the higher the line is, the more likely it is that they will say they are planning on voting for Donald Trump.

As you can see, Republicans were much more likely to support Donald Trump than Independents, and even more so than Democrats. That's not surprising; we would have expected that. What's more interesting is the effect that anti-intellectualism has. In all three groups (but mostly with Independents... just like we would expect), those with higher Populist Anti-Elitism scores were more likely to say they were planning on voting for Donald Trump than those scoring lower on the scale.

Simply put, anti-intellectualism mattered, even when we controlled for a person's party identification. Those exhibiting greater animosity and resentment towards those who are highly educated, were significantly more likely to support Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton.

Putting These Findings Into Context

So, what does this all tell us about what happened this election?

It perhaps gives us some insight into why many of the high-profile renunciations of Donald Trump we heard during the campaign seemed to have so little effect. Newspaper editors, national security officials, former Presidents, government officials, and conservative and liberal pundits alike lined up in their vocal and detailed opposition to a Trump presidency over the course of the campaign. However, most of these appeals appear to have fallen on many deaf ears. Clearly, it seems that many of Trump's supporters felt they have lost their voice in the nation's political discourse (if they had it at all) and resent the way they've been talked down to, and about, by the "intellectual elite."

You may have seen memes circulating around the internet featuring a quote by noted science fiction author Isaac Asimov like the one below:

While it gets to the heart of Hofstadter's analysis of American culture that drove the research project I'm discussing here, this meme has always made me a little uncomfortable. Whether you agree with its sentiment or not, to those with less education it is likely to be seen as an arrogant criticism of "average Americans." It's an important lesson: If you want to convince someone that you have relevant and important information you feel they should know, insulting their intelligence is probably not the best way to preface your remarks. If they think you don't respect them, they're likely to return the favor. It's probably why this survey item is so influential in my measure of Populist Anti-Elitism:

The Obligatory Nerdy References Section

For the nerds reading this, or if you want to expand your nerdy credentials, here are the specific works I mentioned in this post:

Gauchat, Gordon. 2012. "Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010." American Sociological Review. 77: 167-187

Hofstadter, Richard. 1963. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. New York: Knopf

Rigney, Daniel. 1991. “Three Kinds of Anti-Intellectualism: Rethinking Hofstadter.” Sociological Inquiry. 61: 434-451.

While opposition to such things as teaching evolution in public schools can logically be connected to religiosity, the same cannot necessarily be said about other issues where public perceptions are often at odds with the conclusions of the scientific community. Battles over climate change and the safety of vaccinations and genetically modified organisms in food come to mind. Opposition to the evidence and conclusions presented by the scientific community on these issues seem less likely to be due to religious objections but simply due to a related, but distinct, fourth dimension of anti-intellectualism:

- Anti-Scientific Skepticism - The belief that science, and especially those who practice it, are motivated by biases (political or otherwise) that render their findings and conclusions suspect, not on religious grounds but likely through a lack of scientific understanding, motivated reasoning or a combination of both.

From that basic framework, I developed a battery of Likert-type survey questions for each construct (In non-nerd speak: I presented them with statements like those presented below and then asked them to indicate on a 5 point scale ranging from 1 which meant they strongly disagreed with the statement to 5 which meant that they strongly agreed with the statement). Examples of the items in each dimension are presented below:

A lot of problems in today’s society could be solved if we listened more to average citizens than we did to so-called experts. [Populist Anti-Elitism]Anti-Intellectualism in 2016

Universities and colleges place too much emphasis on subjects like Philosophy and the Arts and not enough on practical job training. [Unreflective Instrumentalism]

Often it seems that scientists care more about undermining people’s beliefs than actually solving problems. [Religious Anti-Rationalism]

Science has created more problems for society than it has solved. [Anti-Scientific Skepticism]

With these questions and others like them, I created four anti-intellectualism scales (one for each dimension) by taking the average score across the items within each dimension. I included these questions along with a series of other questions about the campaigns and the candidates running this year to a national sample of 1220 Americans from June through August earlier this year.

The results seem to confirm that Donald Trump's anti-intellectual/anti-establishment rhetoric appeared to strike a chord with a number of individuals. As the figure below shows, Trump supporters were significantly more likely than those supporting Clinton to hold anti-intellectual views on each dimension. (p < .001, which, in non-nerd speak, simply means that we can reasonably conclude that the differences we see here in the anti-intellectualism scores between Clinton and Trump supporters are real and not simply due to the fact that we only talked to 1220 people).

Using Anti-Intellectualism to Predict How a Person Will Vote

I took this a step further to see if we could use the anti-intellectualism scores to estimate the probability of supporting Donald Trump, while controlling for party identification. To put it more simply: We know that Republicans are more likely to support Donald Trump than either Independents and Democrats. Does anti-intellectualism make Independents, and even Democrats, more likely to support Donald Trump? Are Republicans who score low on the anti-intellectualism scale less likely to support him than fellow Republicans who score higher?

To answer those questions, I did some (more) nerdy stuff. I ran a logistic regression with the vote intention question as the dependent variable and party identification and the anti-intellectualism scales as independent variables Logistic regression is a statistical technique we nerds use when we want to see if certain variables (in this case a person's party identification and their anti-intellectualism scores) can help us predict what someone is going to do or say when they're given two choices. In this case, those two choices were either saying they were going to vote for Donald Trump, or for Hillary Clinton. (Yes, I know there were other choices, but there weren't enough people in my survey who said they were planning on voting for Gary Johnson, Jill Stein, or someone else... so this works).

Simply put, it's basically a more rigorous test of the influence of anti-intellectualism on a person's decision about who they were planning on voting for than the figure above. When I ran all the variables together as predictors of intended vote choice, only one of the anti-intellectualism dimensions ended up being a significant in addition to party identification: Populist Anti-Elitism.

The figure below shows how a person's party identification (whether they consider themselves a Democrat, Independent, or Republican) and their populist anti-elitism score effects the likelihood that they would indicate they were planning on voting for Donald Trump. Each line represents people in each party identification category. As the lines move across the chart to the right, it indicates people with higher anti-intellectualism scores, and the higher the line is, the more likely it is that they will say they are planning on voting for Donald Trump.

As you can see, Republicans were much more likely to support Donald Trump than Independents, and even more so than Democrats. That's not surprising; we would have expected that. What's more interesting is the effect that anti-intellectualism has. In all three groups (but mostly with Independents... just like we would expect), those with higher Populist Anti-Elitism scores were more likely to say they were planning on voting for Donald Trump than those scoring lower on the scale.

Simply put, anti-intellectualism mattered, even when we controlled for a person's party identification. Those exhibiting greater animosity and resentment towards those who are highly educated, were significantly more likely to support Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton.

Putting These Findings Into Context

So, what does this all tell us about what happened this election?

It perhaps gives us some insight into why many of the high-profile renunciations of Donald Trump we heard during the campaign seemed to have so little effect. Newspaper editors, national security officials, former Presidents, government officials, and conservative and liberal pundits alike lined up in their vocal and detailed opposition to a Trump presidency over the course of the campaign. However, most of these appeals appear to have fallen on many deaf ears. Clearly, it seems that many of Trump's supporters felt they have lost their voice in the nation's political discourse (if they had it at all) and resent the way they've been talked down to, and about, by the "intellectual elite."

You may have seen memes circulating around the internet featuring a quote by noted science fiction author Isaac Asimov like the one below:

While it gets to the heart of Hofstadter's analysis of American culture that drove the research project I'm discussing here, this meme has always made me a little uncomfortable. Whether you agree with its sentiment or not, to those with less education it is likely to be seen as an arrogant criticism of "average Americans." It's an important lesson: If you want to convince someone that you have relevant and important information you feel they should know, insulting their intelligence is probably not the best way to preface your remarks. If they think you don't respect them, they're likely to return the favor. It's probably why this survey item is so influential in my measure of Populist Anti-Elitism:

Highly educated people have an arrogant way about them.

The Obligatory Nerdy References Section

For the nerds reading this, or if you want to expand your nerdy credentials, here are the specific works I mentioned in this post:

Gauchat, Gordon. 2012. "Politicization of Science in the Public Sphere: A Study of Public Trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010." American Sociological Review. 77: 167-187

Hofstadter, Richard. 1963. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. New York: Knopf

Rigney, Daniel. 1991. “Three Kinds of Anti-Intellectualism: Rethinking Hofstadter.” Sociological Inquiry. 61: 434-451.

No comments:

Post a Comment